The History of Diamond Cutting - From Pre-History to the Brilliant Cut

There’s nothing quite so alluring as a pretty gem, sparkling from a magnificent cut. The roots of gem cutting aren’t nearly as classy, but they are none the less important. Early man in the stone age discovered that some rocks are harder than others, and the core of lapidary (or stone cutting) was born.

Living in an unforgiving world where rock was the greatest resource meant that a smart caveman was the caveman who had tools. A rock with a sharp surface could mean the difference between life or death, in a world without knives or metal. By the end of the stone age, copper and bronze had largely taken ahold of our fascination for poking things with pointy objects, but for millions of years if a job was to be done it had to be done by stone.

It’s hard to imagine that our prehistoric ancestors weren’t just as pulled to shiny objects as we are today. Indeed, graves from the Paleolithic era have revealed skeletons adorned in rows of beads that must have been at some point a type of jewelry. Perhaps there was a function, perhaps not; when you get right down to it there’s no need to justify the presence of jewelry on ancient man. They worked in stone, wanted to be fashionable, and realized that they could wear it just as much as they could use it. The rest was history.

Man Conquering Stone: A Major Step in Human History

When you think of a caveman attempting to make something out of stone, you inevitably conjure up the image of an ape-like creature with an enormous forehead bent over a rock and smacking it to death with another harder rock. Reality was much more sophisticated and involved four processes that formed the cornerstones of early lapidary: flaking, drilling, bruting, and smoothing.

Flaking was the very first of the art, and perhaps the inspiration for our visualization of the caveman bent over his primitive creation. If a prehistoric human ever spotted flint or a similar siliceous stone, he would quickly snatch it up because he knew that he could easily chip it and create a sharp edge. But flint didn’t exist in every region, so what did man do then? Sandstone, quartz, and obsidian were familiar and just as precious as flint. Man might not have known as he smacked away at a stone that he was engaging in primitive geometry, but inside each stone that he shaped existed a matrix which responded to the pressure of a blow. The more he experimented with shaping the perfect stones for his needs, the more he realized that certain rocks were harder (and therefore more useful) than others.

Drilling was used for more ornamental purposes and can be linked to the primitive form of a necklace. By putting a hole through a stone, you suddenly had a way to carry it around with you that didn’t involve your hands. But there’s no point in wearing a stone against your bare skin if its rough and unseemly. Man has been suffering with vanity since the dawn of time, and it seemed he was quick to realize that he could smooth a stone just as easily as he could sharpen it.

Between the Paleo-Neolithic era, a time as far back as 10,000 BC, man was starting to get a true foothold in his world and understand the science around him. In particular, he noted that all the shavings he got from flaking and drilling a stone could serve yet another purpose: that of smoothing. A dash of river water and some sand from drilling created a paste. Rubbing this against stones created the same smooth finish that you’d find in a river rock… much more pleasant against the skin. And thus, the first beads came into existence.

From Jewelry to Statues and Story Telling

But modern man wasn’t content to just wear some pebbles and call it a day. He saw the world around him and wanted to know his place in it. He wanted to build idols to gods that he thought might help him with a better harvest or more game. He even wanted to make an image of himself, which is slightly vain but understandable in a world without mirrors. So how did ancient man go about creating a statue with nothing more than his wits?

Lapidary and the formation of ancient statues have a great deal in common as the practice of one is built on the experience from the other. By the year 3,000 BCE, lapidary had evolved from simple stones to cylinders made of serpentine. These items were worn like amulets and were taken off to be pressed into wet clay to show a story when rolled. Jewelry was starting to serve a function.

If you could cut and shape a statue, you could most certainly cut and shape a gem. You started by cutting a small chunk of rock from a larger chunk; obsidian was the best agent for this job as a hard stone with an excellent cutting edge. As soon as you got a chunk of stone that you were happy with, you started to shape it with emery, also known as “corundite”. This is the same abrasive grain used today in the shape of stones. When you were finally happy with the shape, you smoothed it down with corundum powders made into a watery paste. This method allowed ancient lapidaries to polish every stone in existence, except one: diamonds.

Using Diamonds as a Store of Value… 2600 Years Ago

The diamond that we so adore today was first discovered and appreciated for its unique properties around the 6th Century BC in what we would now refer to as Ancient India. The wealthy citizens of the Mahajanapada Empire were the first people in recorded history to find a use case for diamonds: holding value. Banks did not exist that long ago, so it was up to individuals to keep track of the entirety of their wealth. Converting that wealth into diamonds made that much easier. The common practice of storing wealth in diamonds and precious gemstones eventually led to the government developing a specific standard of measurement for translating precious stones into precious currency. A manuscript dating between 320-296 BCE entitled “Arthashastra” (“The Lesson of Profit”) tells us of a system of testing gemstones to control the trade of precious gemstones, including diamonds.

The unit of measure that these ancient peoples used was called a “Tandula”, which was equivalent to the weight of a single grain of rice. Their currency, was called the “Rupaka”, and according to a price list from the 3rd Century BCE, a diamond that weighs 20 Tandulas was worth 200,000 Rupaka.

Learning to Polish the Unbreakable Stone - The Controversy Over Ancients Polishing Diamonds

There is a lot of controversy surrounding who was the first person to discover that diamonds could be polished using diamond dust. There has not been any evidence of an ancient polished diamond discovered by archaeologists in any region, and there is no mention by Pliny or any other ancient writer of using diamond dust as a polishing compound or even that it is possible to polish a diamond.

In fact, ancient peoples were actively against polishing diamonds. They viewed diamonds as magical and believed if the stones were polished they would lose their powers.

According to Persian writer Al-Biruni in “The Comprehensive Book on Precious Stones”, published in the 10th Century CE, “The people of India prefer the diamond that is unbroken and whole in shape with its sides sharp. They do not like diamonds with broken sides. In fact, they tend to regard this as an evil portent.”

Early Evidence of Diamonds Being Used for Cutting/Polishing

While there is no official evidence of ancients polishing a diamond, it is important to never underestimate the power of ancient genius and determination. Let us not forget how Archimedes of Syracuse and Heron of Alexandria invented the steam cannon and steam engine respectively. These two innovators were way before their time. When our modern civilization rediscovered these inventions in 1712 (well over 1500 years later), they were considered some of the most important inventions of the time, igniting the first true Industrial Revolution.

The “Arthashastra” (4th century BCE) makes no mention of using diamond dust as a polishing compound (the only way to polish a diamond), but it does suggest that they were regularly being used for cutting holes in other substances: “the stone which is cut with a blade, or which is worn out by repeated friction, becomes useless, and it’s benevolent virtue disappears; the stone, on the contrary, which is absolutely natural has all its virtue.”

A few centuries later, Roman historian Pliny the Elder wrote about diamonds being used by engravers in his “Historia Naturalis” (77-79 CE). He described diamonds as “the substance that possesses the greatest value, not only among precious stones, but of all human possessions...These particles are held in great request by engravers, who enclose them in iron, and are enabled thereby, with the greatest facility, to cut the very hardest substances known.”

This does not state that diamonds were used to polish stones, but we do know Romans were innovative lapidaries, as can be best seen through the 2000 year old sapphire cameo ring worn by Caligula, who ruled Rome from 37-41 CE.

It’s not unrealistic to think Romans may have used diamond dust as a cutting or polishing agent, but we don’t get a real reference of using diamonds to polish stones until around 500 AD, when “Ratnapariska”, a Sanskrit document written by Buddhabhatta, states, “Wise men should not use a diamond with visible flaws as a gem; it can be used only for polishing of gems, and it is of little value.”

This at the very least suggests that diamond dust was being used to polish other gemstones, over 800 years before Europeans are credited with polishing the first diamond. Did these ancient Indian people attempt to use this technique to polish a diamond? We may never know.

Revisiting our Persian friend Al-Biruni a few centuries later, he states “Some persons are inclined towards the belief that the diamond can cut all the other stones and bore a hole through them as it possesses the characteristics of a fiery species. Its fire penetrates other things from one end to the other; that is, its fire makes a hole through them and cuts through the distance of its sides.” He also states “…Diamond cuts ruby, while the latter can cut the other jewels. Diamond is not affected by anything superior to it or by anything that is inferior.”

Even more intriguing, in the same manuscript, Al-Biruni mentions a man who describes a diamond which has been engraved. Granted he finds this assertion laughably ridiculous: “Just see for yourself how careless Utarid bin Muhammad has been in his description of the diamond in his book. On one occasion he says that the diamond is not affected by anything. Then, forgetting what he has said, he writes that there was a diamond stone in which was engraved a woman standing upon four horses.”

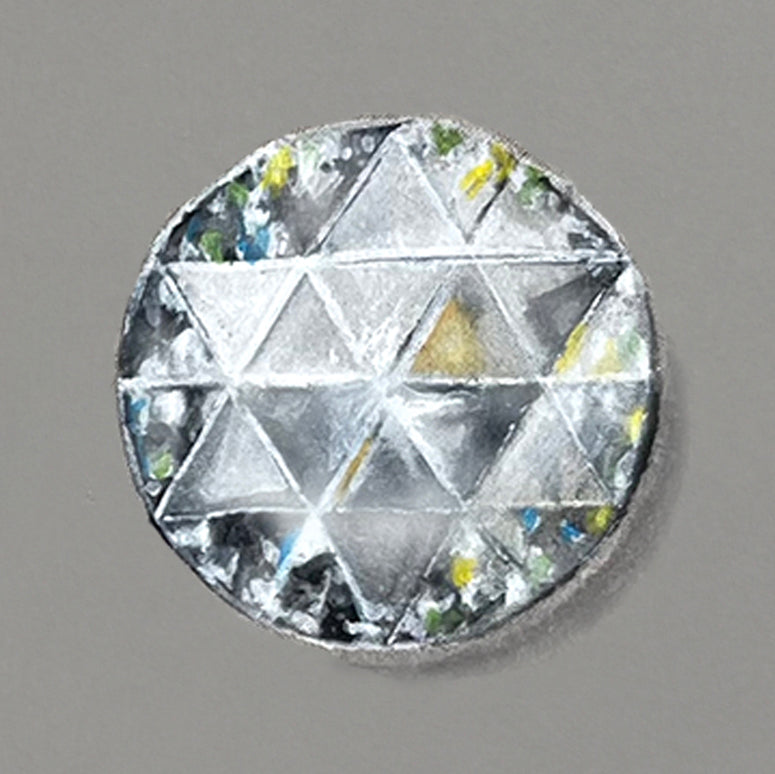

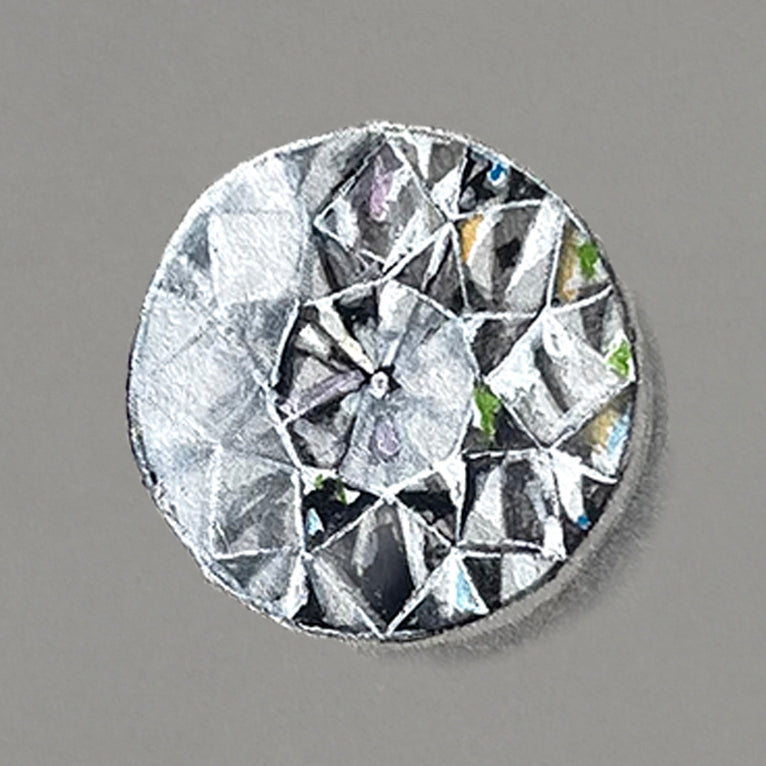

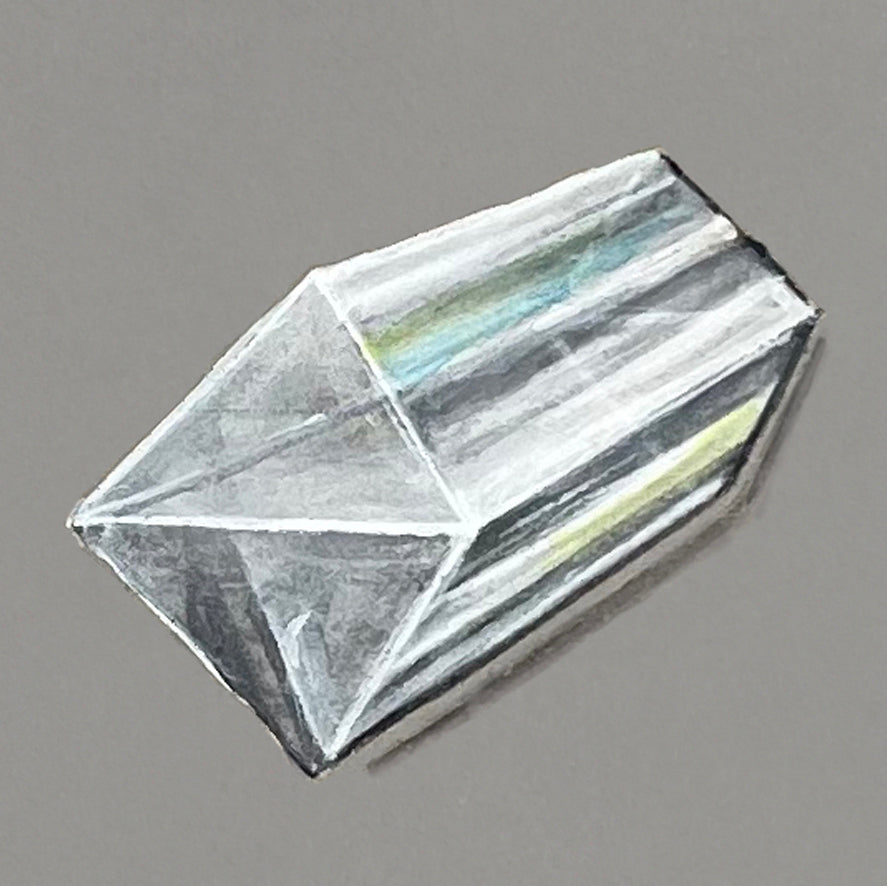

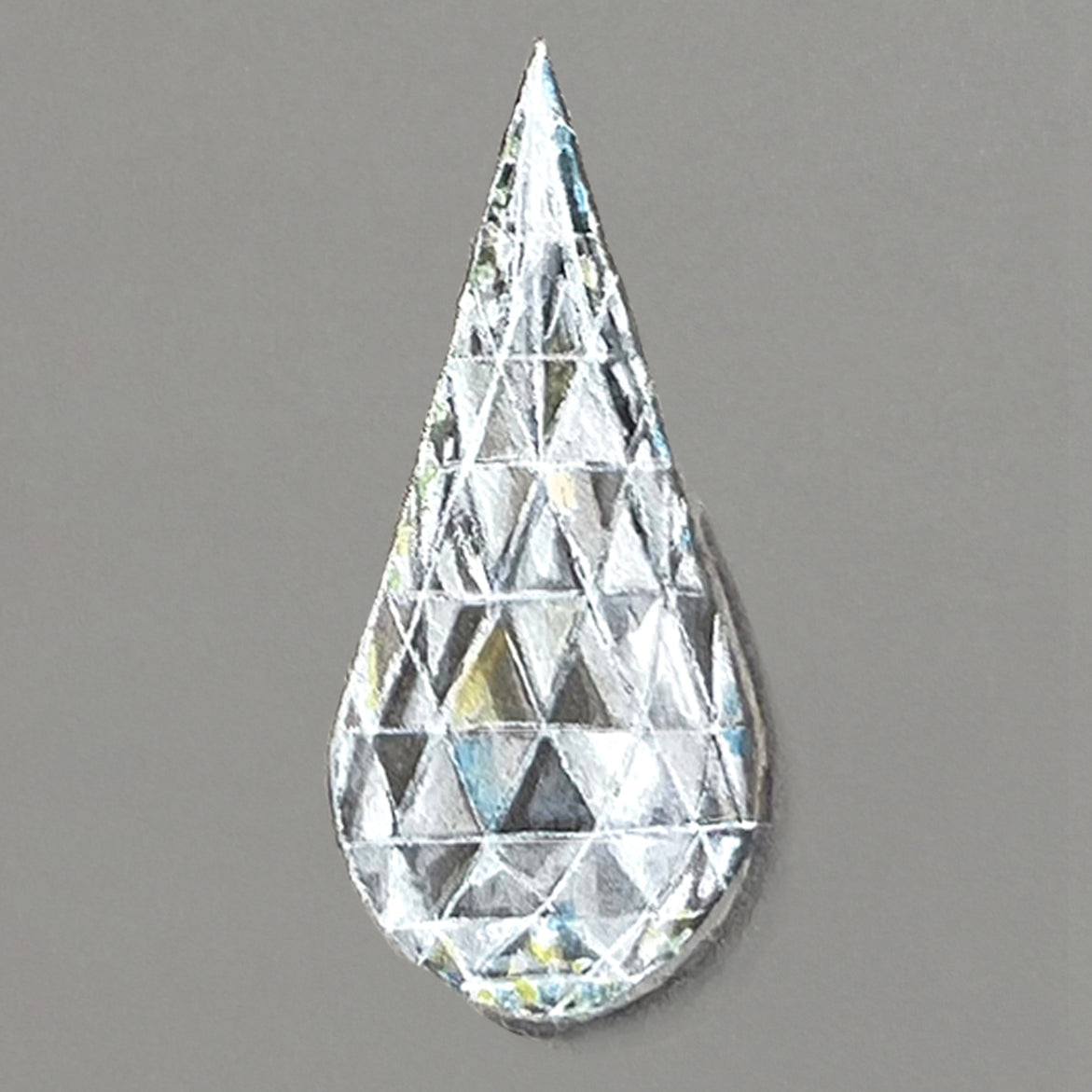

Another small bit of evidence comes from the Tanjavur Temple inscriptions from items offered to the deities. According to Jack Ogden in Diamonds: An Early History of the King of Gems, the diamonds listed in these inscriptions are categorized as “diamond crystals, smooth diamonds, square diamonds with smooth edges, flat diamonds with smooth edges, and round diamonds.” This could potentially mean that it had been discovered in India that diamond dust could polish a diamond by the 10th century. At the very least, it shows that diamonds were commonly being worn in jewelry by this point.

Realistically, it seems most likely that diamonds were used as tools for drilling holes in beads and for carving other stones, but there is no significant evidence of diamonds being used to cut or polish diamonds.

Diamond Dust Finally Exists (Documented Anyway), But It’s Not Used to Polish Diamonds…

By the 13th century, it is clear through collections of Islamic sources that diamond dust had been discovered. Ironically, it was seemingly used exclusively as a poison or for an invasive procedure (that I’m definitely not going to go into) designed to help remove kidney stones. There does not appear to be any indication of diamond dust being used in the cutting or polishing of diamonds at this point in history. Fun fact, diamonds are not very effective when used as a poison, but we still don’t recommend eating them.

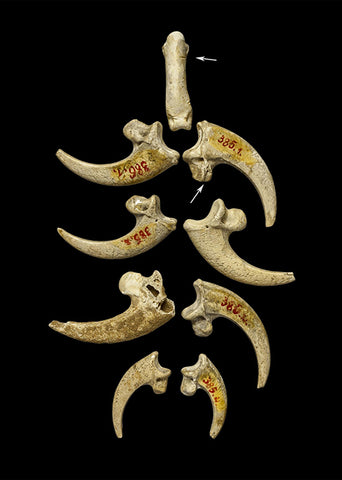

White Tail Eagle Talons From What Is Likely to Have Been a Neanderthal Necklace Dating Back Approximately 130,000 Years. The Arrows Identify Cut Marks - Credit: From: Radovčić D, Sršen AO, Radovčić J, Frayer DW (2015): "Evidence for Neandertal Jewelry: Modified White-Tailed Eagle Claws at Krapina."

White Tail Eagle Talons From What Is Likely to Have Been a Neanderthal Necklace Dating Back Approximately 130,000 Years. The Arrows Identify Cut Marks - Credit: From: Radovčić D, Sršen AO, Radovčić J, Frayer DW (2015): "Evidence for Neandertal Jewelry: Modified White-Tailed Eagle Claws at Krapina." A Flint Hand Axe dating back to 120,000–30,000 BCE Discovered in Egypt - Credit: Cleveland Museum of Art

A Flint Hand Axe dating back to 120,000–30,000 BCE Discovered in Egypt - Credit: Cleveland Museum of Art A Black Marble Cylinder Seal Dating Back 3000-2700 BCE in Ancient Mesopotamia - Credit: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

A Black Marble Cylinder Seal Dating Back 3000-2700 BCE in Ancient Mesopotamia - Credit: Los Angeles County Museum of Art A Carved Ceylon Sapphire Intaglio Featuring a Ptolemaic Princess as the Goddess Nike - 2nd century BC - Given the Hardness of Sapphire, there is a Possibility this Stone was Carved Using a Diamond - © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons

A Carved Ceylon Sapphire Intaglio Featuring a Ptolemaic Princess as the Goddess Nike - 2nd century BC - Given the Hardness of Sapphire, there is a Possibility this Stone was Carved Using a Diamond - © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons A Statue of the Great Persian Polymath, Al-Biruni, located at the UN Offices in Vienna

A Statue of the Great Persian Polymath, Al-Biruni, located at the UN Offices in Vienna