Table Cut

Sometimes in history, the most remarkable innovations are also the simplest. For thousands of years, the natural shape of the diamond had served as the benchmark for perfection. But its towering physique left much to be desired for the wearer, especially in a world where Christianity was overtaking the worship of nature as the “modern world’s” most practiced religion. Like Icarus soaring for the sun, or a delicate chain holding a heavy pendant, it was only a matter of time before any rough diamond or point cut would begin to diminish with wear and tear. So what do you do with the stone then?

The answer was obvious, if a little obtuse: just polish the pointy parts to make the top flat.

The table cut, like its namesake, came from a desire to have a flat surface that you could work upon. The sheer brilliance (pun definitely intended) of a table cut is its ability to alter the way light interacts with a diamond without requiring significant alterations to the stone. It doesn’t need a lot of carefully placed facets, a mere slice off the top or heavy handed polish will do. By taking the tip off of a point cut, the new shape reveals four main, natural facets on the pavilion of a gem. You might be asking yourself, ‘I could have sworn a pavilion was a porch’, but when it comes to lapidary, a pavilion refers to the part of a cut gem that is below the girdle.

With it's new shape, people could now appreciate the beauty of a diamond and explore the magic that lives inside of them on a much different level than was previously possible with a point cut. This cut has been referred to as the ‘grandfather cut’ for its prodigies in the form of emerald cuts, carre cuts, mirror cuts, and French cuts. Each of these descendants were born during the Renaissance, although the emerald cut would not be transferred to a diamond for several centuries.

How Did the First Diamond Cutters Polish a Diamond?

The earliest diamond cutters had finally accomplished the long sought after goal of fashioning a diamond. The secret to their success was finally realizing that although diamond was the hardest substance in the world, it could still polish itself. The way they did this was most likely by putting a paste made of diamond dust combined with oil or water on a flat surface and rubbing the stone they wanted to polish repeatedly across it.

Unlocking The Magic Inside A Diamond

Diamonds are impossible to polish, except with the dust of other diamonds. Diamonds were likely used to drill, carve, and possibly polish other gemstones much earlier in history, and eventually, jewelers and lapidaries began to experiment with what else they could do with the dust like diamond particles that would break down over time. Diamond grit could be manufactured into a paste, and by savagely rubbing a point cut diamond into this grit, you could eventually wear away the point until there was a flat surface. This rather crude grinding method is known as ‘bruting’, and it still serves as the first step in fashioning a diamond today. Collecting the fragments of diamonds was a simple matter of having a bruter’s box, which was a small box beneath a jeweler’s table where dust could be collected during manipulations. By removing the top point of a diamond, an inner fire was unlocked beneath. Light could now be reflected from within the diamond back into the wearer’s eyes. In lamplight, the diamond could sparkle with an undeniable brilliance.

Beyond this flashy façade was also the desire to prevent damage. It was tough work being wealthy in the 1500’s. Lords were the servants of their kings and could be called into battle at the drop of a hat. Hunting large game, mock fighting, riding horses: all of these things could take a toll on the jewelry you wore. Any crack or natural surface inclusion in a natural diamond or point cut could result in deeper damage to stone; the birth of the table cut offered a way to keep diamonds safer for longer.

The Father of Modern Diamond Cutting?

The birth of the table cut came directly from the workings of a true genius: Lodewyk van Bercken, of Bruges, Flanders. Commonly referred to as the Father of Modern Diamond Cutting, Bercken’s claim to fame comes from inventing the skeif in 1476. The skeif is a horizontal metal wheel, which is covered with diamond dust and oil. By using oil instead of water, the diamond particles are kept in place on the wheel instead of slinging off from centrifugal force. This created a way to cut a stone with intense control that allowed for the succession of more in-depth and complicated cuts.

Lodewyk van Bercken was fascinated with the symmetry and reflection inside of a diamond. He is credited with not only inventing the skeif, but also with inventing the rose cut, briolette cut, and the pendeloque cut (which was essentially the first pear shape). This makes Lodewyk van Bercken undoubtedly the most significant man in the history of diamond cutting.

Is that what really happened though? Probably not…

These stories all stem from Robert de Berquen (1615-1672) who claims that his ancestor invented the process of cutting diamonds with diamond powder in “a singular spirit of genius”. According to the historical digging of Jack Ogden in Diamonds: An Early History of the King of Gems, there is no evidence that Lodewyk van Bercken even existed at all. Granted records from that time are not the best, but still, if he made all of these incredible discoveries, wouldn’t you expect his name to be mentioned in at least one historical document or by one historical source?

Additional evidence against these claims is a gold gem encrusted goblet, which is currently is the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna featuring a polished pear shape diamond. The Burgundian Court Goblet, as it is now known, was mentioned in an inventory dating back to 1467, 7 years before Lodewyk is said to have discovered the only possible way to polish a diamond.

Myth or historical figure, the persona of Lodewyk van Bercken has been celebrated for centuries. His “contributions” to diamond cutting were commemorated in an 1868 musical play in Antwerp, Berken de Diamantislijper by Karel Versnaeyen. He was further championed in 1906 when a stature was erected by Frans Joris, just a few blocks away from Antwerp’s famous diamond district. The statue depicts Lodewyk holding a diamond in his hand and a baby angel flying above.

Regardless of whether Lodewyk van Bercken created the skeif, made some minor advancements in diamond cutting, or never existed at all, one thing that all diamonds historians can agree on is that the 15th century is when the first monumental strides in diamond cutting began to take place.

The First Documented References to Table Cut Diamonds

The earliest refence to a table cut diamond, amongst documented historical records, comes in the form of a pawn receipt from Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I in Nuremberg (1491). The list of jewels includes two bracelets, each set with table cut diamonds which had been “lozenged”.

There are several other references to table cut diamonds amongst inventories of European royalty over the following century. In the mid-sixteenth century, Italian goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini stated that diamonds had “three lovely shapes” (table, faceted and point). The reference to faceted stones is most likely describing diamonds which were simply polished and given facets to enhance their natural shape, similar to a Mughal cut.

Famous Table Cut Diamonds

Most surviving pieces of diamond jewelry dating back to the 1400-1600s are going to contain table cut diamonds in some fashion. We also see some examples of large table cut diamonds in classical art; for example the ring finger ring on the Portrait of Pope Julius II by Raphael in 1511-1512. Unfortunately, we don’t see many examples of diamonds of a significant size surviving in a table cut today. One example of a significant table cut stone we do still have today was most likely recut from an even more famous table cut diamond in the early 1800s. That stone is the Darya-i-Noor diamond.

One of the most significant table cut diamonds in history, known simply as “The Great Table” diamond, was first documented by famed French gem merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689). Tavernier said about the storied diamond, “It is a stone which weighs 176 1/8 mangelins, which make 242 5/16 of our (old) carats. When in Golconda, in the year 1642, I was shown this stone, and it is the largest diamond I have seen in India in the hands of dealers. The owner allowed me to make a casting of it, which I sent to Surat to two of my friends, calling their attention to the beauty of the stone and to its price, which was 500,000 rupees. I received a commission from them to offer 400,000 rupees for it, but it was impossible to come to terms at this price.”

The magnificent diamond is said to have been owned by the first Mughal emperor and passed down through many generations. The lineage of the stone is fairly well documented. In 1791, Sir Harford Brydges, a British diplomat hired by the Shah to sell some diamonds, was fortunate enough to lay eyes on the diamond and noted that the stone was just as Tavernier described.

Notably, Fath Ali Shah, the second Shah of Qajar Iran and a lover of gems possessed the diamond during his reign (1797-1834), it is during this period that the stone is believed to have been broken.

This was first theorized by three Canadian gemologists who were invited to inventory the Iranian Crown Jewels in 1969. They became very interested in two large pink diamonds, the Darya-i-Noor and Noor-ul-Ain diamonds, which were very similar in color and clarity. After an in-depth analysis, the gemologists concluded that the diamonds had been cut from the same piece of polished rough: The Great Table Diamond. Based on their measurements and calculations, they determined that the Great Table Diamond measured 56.3 x 29.5 x 12.15mm. Based on these dimensions, the Great Table Diamond would be estimated to weigh approximately 370-400 carats based on mathematical formulas to determine weight, a good bit larger than the 242 5/16 carat measurement provided by Tavernier.

The Darya-i-Noor and Noor-al-Ain diamonds are both currently a part of the Iranian National Jewels, which are held at the National Treasury of Iran in Tehran.

A Table Cut Diamond Ring Set in Gold with Enamel Accents - Photo Courtesy of

A Table Cut Diamond Ring Set in Gold with Enamel Accents - Photo Courtesy of  Statue of Lodewyk van Bercken located a few blocks away from Antwerp's Diamond District

Statue of Lodewyk van Bercken located a few blocks away from Antwerp's Diamond District Portrait of Pope Julius II painted by Raphael, Circa 1511-1512. It appears he is wearing a large table cut diamond ring.

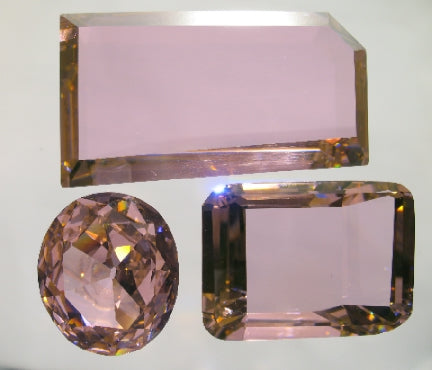

Portrait of Pope Julius II painted by Raphael, Circa 1511-1512. It appears he is wearing a large table cut diamond ring. Replicas of the Great Table, Darya-I-Nur, and Nur-al-Ain - courtesy of

Replicas of the Great Table, Darya-I-Nur, and Nur-al-Ain - courtesy of