Rose Cut

Diamond Cutters are the New Alchemists

With the invention of the iron skeif and the discovery that diamond dust could be collected and used to polish diamonds, lapidaries were poised to unlock new potential in the most valuable and elusive stone known to exist. Combine that with new trade routes opening up with the East and an increased amount of wealth accumulating in royal coffers, and the late 15th century set the stage for a significantly increased interest in diamonds and the ability to maximize their beauty. Following the traditional look of the point cut and table cut, the next step in maximizing beauty within a diamond came from adding more facets and making the stone sparkle. That evolution is what we today refer to as the rose cut.

The shape of a rose cut diamond would be most closely directed by the original shape of the rough stone. For a lot of stones, particularly smaller ones, there was a cleavage point where they were cut to serve as a flat base, and the upper half of the stone would be domed and riddled with mostly triangular facets.

These beautifully unique stones were always set with a closed back, almost always with black foil of some type behind the stone. Sometimes, jewelers would mix it up and set it over a silver or gold backing, but rose cut diamonds did not reflect the light like the diamonds we are used to today.

Credit for the section title “Diamond Cutters are the New Alchemists” comes from Jack Ogden’s “Diamonds: An Early History of the King of Gems”. It was too good not to use.

Two Different Styles of Rose Cut Diamonds: The Single Rose Cut and The Double Rose Cut

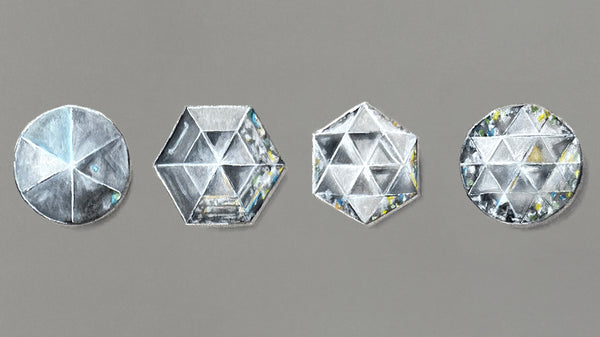

The first was the single rose cut. It had, as the name reveals, a single layer of facets on one side of the diamond. The bottom of the stone was flat, which made it easy to set, but didn’t do much to enhance the sparkle factor. As diamond cutters improved their abilities and experimented, they began to see that more facets improved the way the diamond sparkled. Rose cut diamonds slowly progressed from 6 facets to include 12, 18 or 24 top facets.

Then came the double rose cut, which had a deeper setting and another layer of facets on the underside of the diamond. This extra faceted layer made the stones deeper, so they were more difficult to set as small accent stones, but they were much more striking and full of life as the main focus stone in a piece. These “double rose cuts” are very similar in style to a briolette and are much more rare than the traditional flat bottom rose cuts.

A Much Needed New Source for Diamonds Emerges: Enter Brazil

The timeline now shifts to the early 1700s. Twenty-five years before the fabled Marie Antoinette was even born, India was slowly drying up as a diamond supply for Europe. **Cue horrified gasps from a crowd of pampered French royals.** But help was on the way, in the form of a quiet babbling brook flowing through the uplands of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Among the rich red soils of Jequitinhonha River, poverty ran in abundance along with endemic yellow fever. Covering an area twice the size of Switzerland, this land was arid, meant for cattle farming, and a million miles away in terms of the culture and aesthetic of the French court. But something was lurking in the muddy waters, that rolled and dashed along with pebbles and silt: diamonds. Buckets and cartloads of rough, round diamonds. These gems were far from the angled octahedral points, long considered to be the image of perfection in India. But India’s time in the spotlight was over; changes were coming to the lapidary industry.

This impactful event may have taken place centuries after the introduction of rose cut diamonds, but this is probably the most significant event which helped them achieve widespread appreciation. The Brazilians did not have a desire to keep all of the diamonds in the country like they did in India, and while the Indian mines were slowing production after millennia of mining, the “new world” was just beginning to explore the resources beneath the soil. It wasn’t long before diamonds started flooding into Antwerp (the cutting capital of the world at the time), where rose cut diamonds were being churned out at record pace. The rarest, highly coveted gemstone in the world just became much easier to access.

A New Innovation for Diamond Cutting – Wax Candles

The second important development during this time in lapidary history came not from a gem, but the head of a sperm whale, where a waxy substance known as spermaceti is created to allow the whale to float and sink as it wishes. While this may be abhorrent by today’s standards, whaling had been a common practice since prehistoric times. In the era of the 17th century Europe, hunting whales was the source for the highly desired whale oil. The blubber of a sperm whale was especially different, composed heavily of a liquid wax.

Up until the Georgian era, tallow, a type of mutton fat, was commonly used for candles. Even the poorest of men could dip a reed with tallow and have a candle, but the result was such a stink (literally) that candle making had been banned in several cities prior. Suddenly, the use of spermaceti to make wax candles, which did not smell when burning and gave off a cleaner light, flooded the market with affordable wax candles that could make any household shine in the dark.

Diamonds Aren’t Just for Royalty and Nobles

So, how did these two discoveries effect the world of high jewelry, fashion, and beauty? Quite suddenly, the diamond market was being flooded by reasonably affordable diamonds polished into flat-bottomed domes, and now there were brighter candles to allow them to sparkle better. Foaming at the mouth for the chance to look wealthy, this sudden supply shock of diamonds finally opened availability to those beyond royalty and absurd wealth. Everyone, even those unaccustomed to wealth and luxury, now had a chance to look the part of the French nobleman. These large, wide facets glimmered like stars in the low light conditions of spermaceti candles.

Drawbacks to Rose Cut Diamonds

There are mild drawbacks to the rose cut, and it would be biased of us not to mention them since we are trying to describe the full nature of the cut. A rose cut is often done on a shallow diamond with hardly any depth or perhaps even just a part of a stone that was cleaved off a larger diamond. As such, it lacks the sparkle and luster of a brilliant cut. Fewer facets than modern diamonds allow less light to enter the stone, and a flat base means that their light refraction is limited. Rose cuts have a calm, almost ethereal feel to them whereas modern diamonds are full of fire. Another side effect of the limited facets in a rose cut diamond is that imperfections will show up more easily when looking at the stone with the naked eye.

But holding an antique rose cut to the same standard of a modern brilliant cut is just in poor taste. You can use modern technology, lasers and computers, to create a “perfect” sparkling diamond but you can’t recapture the allure and romanticism of the Georgian era like an antique rose cut can. You can’t stare at a modern cut diamond ring and imagine the stories it could tell or the people it would have known. How it must have felt to be the woman who was the first person to receive this ring or pendant or brooch. Was it her first diamond? Was she the first in her family to own a diamond? You’re essentially walking around with a constant inspiration to create your own Bridgerton fan fiction!

Late Georgian/Early Victorian Rose Cut Diamond Earrings in Yellow Gold

Late Georgian/Early Victorian Rose Cut Diamond Earrings in Yellow Gold Depictions of Single-Sided Rose Cut Diamonds with 6, 12, 18 and 24 Top Facets

Depictions of Single-Sided Rose Cut Diamonds with 6, 12, 18 and 24 Top Facets A Georgian silver and rose cut diamond floral design pendant

A Georgian silver and rose cut diamond floral design pendant A Victorian Egyptian Revival brooch featuring a halo of rose cut diamonds

A Victorian Egyptian Revival brooch featuring a halo of rose cut diamonds