Mughal Cut

One of the most stunning and unique old diamond cuts can be found in the Mughal cut, at times referred to as an egg cut. During one of the many trips to India by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, he returned with sketches of Indian cuts, included the Mughal cut. The cut features a flat top, with gently sloping sides carrying a bounty of facets that each bounce off one another to create a deep sparkling weight.

While this half egg diamond is the stone most associated with the Mughal cut, the term became used as a blanket description for diamonds cut in India during the 16, 17th and 18th centuries.

Oddly enough, this cut may have European origins. The stone in question, known today as “The Great Mughal” was actually said to have been faceted by a Venetian diamond cutter. The people of India had perfected the art of cleaving a diamond, but the Europeans still had a healthy advantage when it came to faceting.

The Great Mughal Diamond

The most significant Mughal cut diamond was discovered in 1650 in the Golconda region of southern India. A whopping 787 carats (allegedly), this diamond was gifted to the 5th Mughal emperor by Emir Jemla, a sort of diplomacy mission aiming for peace between their two families. This precious task of peace negotiation was left in the lap of the Venetian lapidary Hortensio Borgio.

Like almost any large stone, this massive diamond (having come to be known as the Great Mughal) featured several inclusions. But Borgio, perhaps moved by the beauty of the raw stone, foolishly decided it would be a good idea to grind away at the Great Mughal until all the inclusions were gone. Essentially, he created a massive rose cut. As you can imagine this didn’t result in the most dazzling cut by today’s standards, but this diamond disco ball must have been mesmerizing none the less. The Mughal emperor, furious that the diamond cutter has reduced the weight of the stone so significantly, was just about ready to whack Borgio’s head off, but in a show of mercy decided just to render the man penniless by forcing him to cough up every last rupee he possessed as a punishment for his idiocy.

That’s the story at least. Is it actually what happened? Who knows, but it sounds good, so let’s roll with it!

Some years later, the son of the emperor, Aurangzeb, came into contact with the famous French gem dealer, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who wooed him with fancy teas, tales of foreign lands, and pretty jewels. In a show of trust and friendship, Aurangzeb decided to offer Tavernier an opportunity to see the stone in person. Tavernier claims that this is the largest diamond he had ever seen, and documented it as weighing 280 carats.

Tavernier bought many important diamonds on this trip (including the Tavernier Blue Diamond, which would eventually be recut and renamed the "Hope Diamond"), but Aurangzeb held onto the Great Mughal. However, he would never get to fully enjoy it. Mughal India was invaded, with Lahore and Delhi both sacked by the Persian ruler Nadir Shah. Shah, looking for spoils of his grand conquest, found the Great Mughal to be of keen interest, and pocketed it before returning to his home in Isfahan. Perhaps a sign of karmatic reaction, the Great Mughal once again rolled off into the unknown, when Shah was assassinated.

Shah was not exactly known for being a kind man in his final years. At full health he had been known to provide well for his troops, but a sudden swooping illness began to turn his mind to ice. He extorted taxes to push money into aggressive military campaigns, and when revolts broke out, he would crush them and build towers from his victim’s skills. These vicious acts would ultimately poison the minds of those closest to him, with his assassination plotted by a group of fifteen (including two of his own family members). Surprised in his sleep, Shah still managed to take out two men before succumbing to his wounds.

It is possible that one of these thirteen remaining assassinators swiped the Great Mughal. It could just as easily fallen into the hands of any other members of the council before Shah’s territory fell into anarchy and darkness. This is the point where it is lost to history.

The Koh-i-Noor or the Orlov?

There are two arguments for what happened to it next. Some people suggest that The Great Mughal Diamond is now known as the Koh-i-Noor diamond, which was unfortunately recut by Queen Victoria in 1852.

The second storyline is considered by most historians to be the most likely chain of events, if for no other reason than the drawings by Tavernier match the shape of the stone so well. If that’s the case, then the Frenchman over-estimated the weight of the diamond, by about 50%. The second storyline would lead to the Great Mughal becoming known as the “Orlov Diamond”.

Some years later, towards the second half of the eighteenth century, the stone eventually found its way into the hands of an Iranian millionaire named Shaffrass. It caught the eye of Russian military officer, Count Grigory Grigorievich Orlov. Orlov was in a bit of a tricky situation, desperately in love with Catherine the Great of Russia. He’d even gone so far as to help her dethrone her husband in a coup d’etat. The feelings were apparently not mutual. Catherine was growing tired of him and had started eyeing Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin. She’d also expressed interest in the Great Mughal.

So, like so many other lovestruck fools throughout history, Orlov paid gobs of money for the unique diamond, and then gave it as a gift to Catherine in the hopes that she might give up her relationship with Potemkin and return to him. Orlov did not win Catherine’s heart, but she offered him many gifts, including the Marble Palace in Saint Petersburg. She was also kind enough to name the stone after him. The Orlov diamond was placed in a scepter in 1774, where it still sits today. The Imperial Scepter is currently a part of the Russian Crown Jewels.

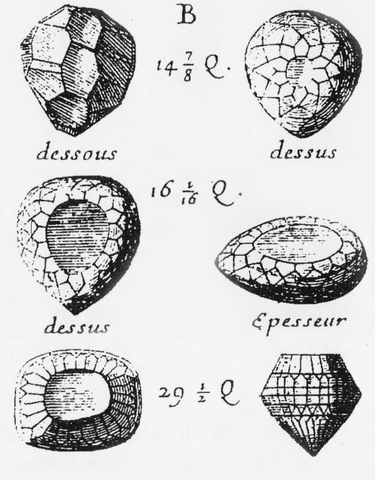

Variations of Mughal cut diamonds documented in the notebook of Jean Baptiste Tavernier

Variations of Mughal cut diamonds documented in the notebook of Jean Baptiste Tavernier The Imperial Scepter featuring the Orlov Diamond - Credit - Bron: Diamonds - Famous, Notable and Unique (GIA)

The Imperial Scepter featuring the Orlov Diamond - Credit - Bron: Diamonds - Famous, Notable and Unique (GIA)